On July 1, 2020, Steve Silberman posted a photo of The New York Times: Understanding Autism magazine and my brain blew up a little. I imagined a nine-part review of the most impactful articles and doing that cool thing on Instagram where you slice the image into nine posts so that it fits together on your wall. Not to mention that it would be the ideal first review: a little bit of current events, and not a huge long book. It was decided. I ordered it.

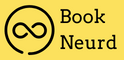

When the package arrived, I cleared my desk and peeled back the cover page to reveal an image of a boy wearing Google glasses. I remembered it from an article that made the rounds in the autistic realm last summer. So, I flipped through and read the first bit, then pulled up the story online. Sure enough, different title, but word for word the same article.

“No way.” I flipped to the next article. And the next. And the next. Every one of the articles in the magazine was previously published online. And not one of them from 2020! In fact, the only unpublished writing is Silberman’s introduction and a gallery of images. So, for $17, I have 24 old NYT articles printed on thick paper.

Weak Central Coherence Theory

Sitting there with the magazine in my hands, I was suddenly back in elementary school staring down at a test I’d just got back, the instructions–bold and underlined–circled in red that I had clearly… ignored? “Lisa needs to slow down to avoid making careless mistakes.” the teacher wrote to my parents. What ensued was a years long game of trial and error: no matter how carefully I read instructions, I’d make a mistake.

I typed “missing important details autism” into Google.

The search brought up article after article talking about one thing: Weak Central Coherence theory. To give a bit of context, people who study us usually talk about three main cognitive skills in reference to autism diagnosis: executive functioning, theory of mind and central coherence. My adventure down the NYT rabbit hole fits under central coherence skills, which is the ability to take all the important details of a situation (this could be a conversation, a written document, etc.), put them together and see the big picture.

This is the idea that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” In other words, rather than just looking at the meaning of each detail alone, you put all the details together and derive a meaning from what they create as a whole. Weak central coherence means that you focus on the details at the expense of the big picture. This cognitive style is often referred to as local bias, global impairment, or the inability to “see the forest for the trees.” Less biased researchers call it detail oriented or detail driven.

The research community is divided on whether there is sufficient evidence to support the theory as a diagnostic tool. Two researchers in support of the theory, Rhonda Booth and Francesca Happé, describe weak central coherence as “the root of characteristic ASD symptoms such as insistence on sameness, attention to parts of objects, and uneven cognitive profile, including savant skills.” Interestingly, even though we don’t seem to go for the higher meaning of a situation naturally, many of us are able to learn to do so.

My Old Friend

Looking back, my relationship with details has always been a bit complicated. For instance, I can spell all 195 countries’ names and point to them on a map. I can remember precisely where on a page I read about a certain idea. Yet, for many years, I struggled with basic things like instructions.

Until I threw a hail Mary in grade 12. I had just bombed my English Provincial exam and really didn’t want to take the whole class over. I noticed there was an English Literature option, and I figured if I could take that and do well, I could retake the English Provincial at the same time and save my GPA. Lucky for me, that semester, Mrs. Nielsen not only taught me the secrets to an A+ English paper, but helped me (through hours of after school study groups) develop an intuitive sense for which details to remember, and which to forget when it comes to painting the big picture.

The Big Picture

There’s a lot more to weak central coherence theory than misjudging magazine purchases and writing papers. Here are some things I’ve found easier and harder because of being detail driven1:

Easier

- Picking out details that others don’t notice

- Specializing in detailed knowledge of a particular topic

- Communicating directly and honestly

- Relaying detailed or nuanced information

- Noticing changes or irregularities in patterns (debugging code, editing, continuity, etc.)

- Recognizing shapes/colours (jigsaw puzzles, photo/film editing, etc.)

- Copying or reproducing drawings, styles, personas, etc.

- Taking tests that focus on the facts

Harder

- Discerning between details that are important and unimportant to the bigger picture.

- “Reading between the lines” (seeing the underlying meaning)

- Summarizing information or relaying the gist of a situation

- Understanding or delivering the punchlines of jokes

- Applying context to words and phrases with double meanings

- Pronouncing homographs (“she didn’t shed a tear” versus “she heard the fabric tear”)

- Applying prior knowledge to new situations

- Creating things from the imagination (as opposed to copying them)

- Taking tests that focus on global concepts

Now, for my NT readers, there is a difference between learning how to do these hard things and being ‘cured’. I don’t sit around in my natural habitat discerning between important and unimportant details for fun. Like the list says, it is harder and I have to focus on it. I definitely spend my off time enjoying getting lost in the more interesting, but insignificant particulars. Which brings me back to the NYT magazine: why are they all old articles, and how come I didn’t realize that before I bought it?

With most of the post written, I allowed myself a little time off-leash to sleuth around. I discovered that nowhere, not in the magazine nor the order details, did it say “This is a collection of previously published works. And after some more googling, I concluded that it isn’t even a genuine NYT magazine (those say “The New York Time Magazine” at the top). In fact, it is only sold on Amazon, where it is manufactured as a “single issue magazine” and printed on demand. I felt vindicated, but still a little annoyed by the deception.

While I try and let that go, I’m curious how central coherence works or doesn’t work for you? Feel free to add to the lists, or maybe share your story of being detail driven. If you need a bit more inspiration, check out fellow blogger Gwendolyn Kanse’s post about her experience.

Oh! And tune in to my next post to find out how things turn out for the Understanding Autism magazine…

- Lists of autistic traits like this often bring up a couple of assumptions that can be harmful. First, that all autistics are the same (we are not.) Second, that autistics are good at certain things and bad at others (that makes as much sense as saying the same about NTs). Third, that if we work hard enough, we can do it all OR if we can’t do it all then we aren’t working hard enough (don’t say this about any humans; it’s rude.)

Really interesting read! I think central coherence is the reason that I learn so slowly. When I’m reading mathematical proofs, on my first read, I spend all my time discerning and categorizing details. Afterwards, I have zero idea what I just read. Then on the second read, I intentionally try to grasp the big picture. In the end though, I think my attention to detail is a strength, it just slows me down. And also, AP Lit was a trainwreck for me until I figured out the difference between the details and the big picture 😂

I love that–attention to details totally is a strength–but it totally slows down learning compared to people who have central coherence in the bag. In school it would be nice to be compared to people with the same cognitive style. That would change a lot! (I felt the same way about math that you did Lit XD)