My neurds, I have a special treat for you today. My friend Hanna, a wicked-inspiring #actuallyautistic woman, has come to us from The Bullsh*t Positivity Project to write a super heartwarming post for you.

Thank you Lisa, for this opportunity to write for your blog! Lisa is a good friend of mine and we both attend the same group for women on the autism spectrum.

A couple years ago, I started to suspect that I was on the autism spectrum. This realization triggered a landslide of emotions, some good, others difficult. My journey since then has been to learn as much as I can about autism and to, for the first time in my life, figure out who I really am. While exploring autism, I learnt plenty, but the story of Temple Grandin and Oliver Sacks captured my heart. It’s truly fascinating and I’m going to share it with you today.

Two Remarkable People and a Story Like No Other

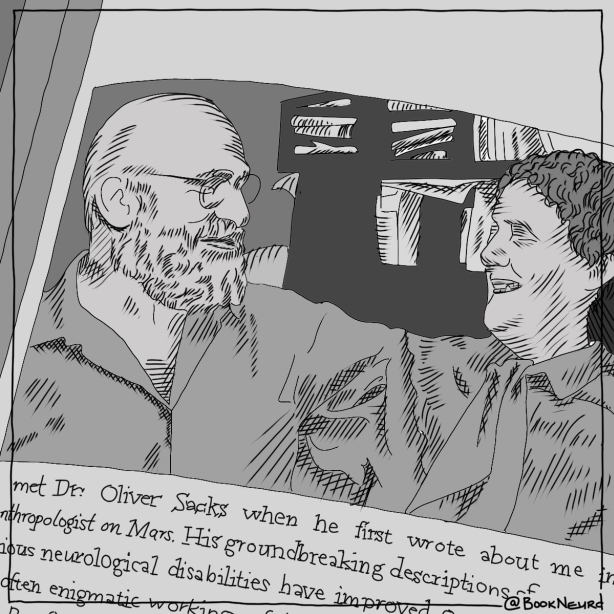

When two remarkable people cross paths, you get a story like no other. Our story begins in 1993 when Oliver Sacks, a prominent neurologist, sets out for Fort Collins, Colorado to write a profile on Temple Grandin, who he describes as “one of the most remarkable autistic people of all.” This post is focused on Oliver and Temple’s fascinating relationship, viewed largely through the lens of Sacks’ profile; it is a relationship that knows deep humility, and an equally deep sense of love (platonic but still heartwarming 🙃).

Meet Temple Grandin: Renowned Animal Scientist and Autism Advocate

Temple Grandin is one of the most prominent figures in the autistic community. In 1986, she published her first book, Emergence: Labeled Autistic, which took the medical community by storm and changed the public’s understanding of autism forever. At the time, such a book was “unthinkable because it had been a medical dogma for forty years or more that there was no ‘inside,’ no inner life, in the autistic, or that if there was it would be forever denied access or expression.” (Grandin & Sacks, 2006, p xiii). Yet here was Temple, intensely articulate, with pages and pages of insight into her experience as an autistic person; numerous books following her first.

Temple’s work, however, does not lie solely in the world of autism. Temple Grandin is also renowned in the livestock industry. She’s “a gifted animal scientist who has designed one-third of all the livestock handling facilities in the United States”. To say that Temple is passionate about cattle is an understatement, Oliver Sacks writes “I was struck by her rapport with, her great understanding of, cattle—the happy, loving look she wore when she was with them.” There’s Temple Grandin for you, but now who is Oliver Sacks? (Grandin & Sacks, 2006)

Meet Oliver Sacks: Quirky Neurologist and Eminent Storyteller

Meet Oliver Sacks, a British-born neurologist who was celebrated for his writing, which he described as clinical tales or “neurological novels”. (Cowles, 2015) With an artistic and even spiritual flair, Oliver told the stories of his patients through a humanistic lens. To give you a sense of his work, Oliver has written about a painter who loses his color vision and undergoes a deep existential crisis (An Anthropologist On Mars), autistic savants (An Anthropologist On Mars), migraineurs and their complex relationship to their condition (Migraine), and a man whose brain was unable to make sense of what it was seeing (The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat), to name but a few. “Ask not what disease the person has, but rather what person the disease has,” is the epigraph for Oliver’s well-known book, An Anthropologist On Mars.

Oliver was quirky too, drawn to motorcycles and the weight lifting culture of muscle beach, an possessed a great love for swimming, music, and the periodic elements. (Cowles, 2015) But now we arrive at the heart of this post which is Oliver’s well-known profile on Temple Grandin. It’s 1993, and Oliver departs for Fort Collins Colorado, where two paths will merge, and the real story begins.

Oliver Is Humble and Makes Space for Temple’s World

While reading Oliver’s profile of Temple, I was struck by his humility towards Temple, specifically his ability to make space for Temple’s world. What I mean by this, is that Oliver allows Temple to define, articulate, and ascribe meaning to her experience as an autistic person. Despite the fact that Oliver is a neurologist and the so-called ‘expert’ of the two, he isn’t the least bit dogmatic and instead allows Temple to craft her own narrative. Much of the profile is devoted to relaying what is important to Temple, that is, topics about which she speaks to him at length and with great passion. Oliver takes the back seat and lets Temple explain her squeeze machine (an invention of hers designed to fulfill her need for deep pressure), her powerful style of visual thinking, her passions (animals and science), her struggles (understanding complex emotions and deciphering social behavior), and her feelings.

Oliver, of course, draws his own conclusions about Temple, but he still demonstrates humility. He frequently uses variations of the phrase “it seems to me” whenever he speculates or theorizes about Temple’s behaviors, abilities, and feelings. For example, at the end of three long paragraphs dedicated solely to relaying Temple’s narrative on various aspects of her experience as an autistic woman, Oliver writes: “There seemed to me pain, renunciation, resolution, and acceptance all mixed together in her voice.” (Sacks, 1993) Throughout the profile, Oliver is not the expert—Temple is. Oliver merely listens and transcribes.

Oliver Sacks Allows Temple to Challenge His Presumptions About Autism

Throughout the profile, Oliver demonstrates humility towards Temple in yet a second significant way. Very frequently, Temple behavior directly challenges Oliver’s presumptions about autism. But instead of anomalizing these moments in an effort to preserve the knowledge of his field, he admits how Temple defies his expectations. There are few stand-out examples of this in the profile. The first one is early on, Temple and Oliver have just met and are driving together when Temple points out a Taco Bell and humorously remarks how it doesn’t look the least bit “bellish.” Oliver writes:

“I was struck by the charming, whimsical adjective “bellish”—autistic people are often called humorless, unimaginative, and “bellish” was surely an original concoction, a spontaneous and delightful image.”

from “Temple Grandin’s Extraordinary Gifts”, by Oliver Sacks in The New Yorker.

Oliver could well have downplayed her humorous remark and explained it away in order to protect the accepted position (of the time) that autistics lacked a sense of humor. But on the contrary, Oliver seems quite delighted to have his mind changed.

Yet another time, excited to show Oliver around a meat-packing plant she helped to design, Temple schemes to smuggle Oliver in, disguised as a sanitary engineer. This is Oliver’s account of their interaction, and how his expectations on autism were challenged, yet again:

“Temple had (…) selected from her hat collection a sanitary-engineer’s bright-yellow hard hat. She handed it to me, saying, “That’ll do. You look good in it. It goes with your khaki pants and shirt. You look exactly like a sanitary engineer.” (I blushed; no one had ever told me this before.) “Now all you have to do is behave like one, think like one.” I was astounded at this, for autistic people, it is said, have no pretend-play, and here Temple had, very coolly, and without the slightest hesitation, determined on a subterfuge and was all set to smuggle me into the plant.”

from “Temple Grandin’s Extraordinary Gifts”, by Oliver Sacks in The New Yorker.

In both of these examples, we see that Oliver is very receptive to having his presumptions about autism challenged. He is bold, for in being prepared to be wrong, he is also prepared for neurology and psychiatry to be wrong. Despite having been trained to adhere to the rigidity and completeness of a diagnostic label, he is humble enough to look beyond it, and to allow Temple to carve out for herself what it means to be autistic.

Oliver Sacks Holds Love In His Heart for Temple Grandin

While reading this profile, Oliver’s profound humility blew me away, but I found Oliver and Temple’s relationship fascinating for a second reason; it entailed a deep mutual love. Not romantic love, per se, but love nonetheless. On Oliver’s part, it is quite clear that he finds Temple endearing. In one smile-worthy anecdote, Temple takes Oliver for a mountain drive, and Oliver, tempted to enjoy a quick swim, asks Temple to pull over so he can rush off on foot to a little lake he has spotted. Oliver’s tale continues:

“It was only when Temple yelled “Stop!” and pointed that I paused in my headlong descent and looked up, and saw that my flat sheet of water, my “lake,” so still just in front of me, was accelerating at a terrifying rate a few yards to the left, prior to rushing over a hydroelectric dam a quarter of a mile away. There would have been a fair chance of my being swept along, out of control, right over the dam. There was a look of relief on Temple’s face when I stopped and climbed back. Later, she phoned a friend, Rosalie, and said she had saved my life.“

from “Temple Grandin’s Extraordinary Gifts”, by Oliver Sacks in The New Yorker.

Doesn’t that last line make you smile? Temple was clearly pleased with this moment of quick observation, and rightfully so, she saved Oliver’s life. And Oliver seems to me, at least, to take happiness and joy in Temple’s bubbling pride—her urge to phone Rosalie and immediately recount her heroics.

To me, endearment is a form of love, and so this anecdote is proof that Oliver held love in his heart for Temple Grandin. But his love for Temple shines even brighter. At the climax of the profile, Oliver recounts that while on their way to the airport, Temple begins speaking to him with a sense of urgency. As always, he captures the words that matter most to Temple:

“This is what I get very upset at. . . .” Temple, who was driving, suddenly faltered and wept. “I’ve read that libraries are where immortality lies. . . . I don’t want my thoughts to die with me. . . . I want to have done something. . . . I’m not interested in power, or piles of money. I want to leave something behind. I want to make a positive contribution—know that my life has meaning. Right now, I’m talking about things at the very core of my existence.”

I was stunned. As I stepped out of the car to say goodbye, I said, “I’m going to hug you. I hope you don’t mind.” I hugged her—and (I think) she hugged me back.”

from “Temple Grandin’s Extraordinary Gifts”, by Oliver Sacks in The New Yorker.

If this isn’t love, then I’m not sure what is. Overcome with emotion, Oliver tries to hug Temple, and again, is respectfully hesitant to define her motives, and feelings, stressing that to his best knowledge, he thinks she hugged him back.

In between the physical affection and strong emotions, I see humility, kindness, and love all wrapped up together in this sentimental goodbye. But there is still more to be said on the matter of love. In response to Temple’s parting words, Oliver is moved, he is not curious. That is, he does not dissect what Temple says, he trusts her—this is how the profile ends, there is no more said on Oliver’s part. It seems that to Oliver, as always, Temple is exactly who she says she is—regardless of labels and preconceived ideas. To strive to see the full humanity in another, despite all the chaos and bureaucracy, despite all the labels and judgments of one’s time, I think, is a powerful and meaningful act of love. And so I say again, in my mind, Oliver Sacks held love in his heart for Temple Grandin.

Temple Grandin Holds Love In Her Heart for Oliver Sacks

There is symmetry in life, and so symmetry in love; Temple held love in her heart for Oliver . To see this, we diverge from the profile and take a step forward through time. After Oliver’s death from cancer, decades after Temple and him collaborated to create her well-known profile, Temple gives a short interview, a tribute to Oliver, for Wired Magazine. In the interview, she says that she had visited Oliver in New York a few times over the years. She continues, with unabashed honesty, saying that Oliver got some of the facts about her house and the squeeze machine wrong for the profile—she had to correct this with the fact-checker (this made me smile). And then she adds, “but when it came to describing my mind, that’s where he got me right.”

This affection and appreciation is both endearing and telling. Temple is a genuine person, she means what she says. But even more endearing, is the fact that she recounts the ‘saving Oliver’s life’ story:

“Then we went up to Estes Park, and he wanted to go and jump in the river. I said, “No, Oliver, you cannot go. There’s a dam there. You might die if you go over that dam. I absolutely cannot let you go in the river.” I stopped him from doing that.”

From “Temple Grandin on How Oliver Sacks Changed Her Life”, by Sarah Zhang in Wired Magazine.

This quote is perhaps an additional sneaky little comment on Oliver’s incredible insight into Temple. Oliver was right—20 years later and she’s still proud of this moment.

But back to Temple’s love for Oliver, where the real heavy hitter comes at the end of the interview. Temple mentions that when she read Oliver’s final essay Sabbath (a reflection on his life and ever-nearing death) she was crying so hard she could barely print it out. Just before he died, after reading Sabbath, Temple Grandin sent Oliver Sacks the following card:

“I started crying at the end of the article when you said, “What if A and B and C had been different?” If that had happened our paths probably would have never crossed. You have made a big difference in my life. Your life has been worthwhile, and you helped many people doing things to enlighten and help others to understand the meaning of life.”

From “Temple Grandin on How Oliver Sacks Changed Her Life”, by Sarah Zhang in Wired Magazine.

Temple Grandin loved Oliver Sacks. And with this symmetry of love, our story ends.

Final Thoughts: A Profoundly Humble Neurologist, an Endearing Animals Scientist, and the Love Between Them

My dear reader, I hope you were as fascinated by Oliver Sacks and Temple Grandin’s friendship as I was. I hope you were awed by Oliver’s profound humility, his efforts to make space for Temple’s world, and his receptiveness to having his presumptions on autism challenged. I hope that you were equally charmed by love—the love that existed between Temple Grandin and Oliver Sacks; the love that came into being when two remarkable people crossed paths.

For more great content, follow my blog, The Bullsh*t Positivity Project on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, Medium, or check out my home base here!

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cowles, G. (2015, August 30). Oliver Sacks, Neurologist Who Wrote About the Brain’s

Quirks, Dies at 82. The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/31/science/oliver-sacks-dies-at-82-neurologist-

and-author-explored-the-brains-quirks.html

Grandin, T., & Sacks, O. (2006). Thinking in Pictures, Expanded Edition: My Life with

Autism (Expanded ed.). Vintage.

Sacks, O. (2019, September 18). Temple Grandin’s Extraordinary Gifts. The New Yorker.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1993/12/27/anthropologist-mars

Zhang, S. (2018, March 8). Temple Grandin on How Oliver Sacks Changed Her Life. WIRED

Magazine. https://www.wired.com/2015/09/temple-grandin-oliver-sacks-changed-

life/